It often feels like we are blessed at the moment, in seeing a freak generation of athletes in every sport, who are pushing the boundaries of what we thought possible of human performance. Each Olympics, we see world record after world record fall, with the majority of world records having been set in the past decade. But what is driving these performances? Are training methods and nutrition massively superior to previous generations, or is something else driving these improvements.

9.58s Berlin 2009

# 10.2s Chicago 1936

Let’s start by comparing the ‘greatest track and field athlete of all time’ Jesse Owen with the fastest man alive Usain Bolt. If you compare their best 100m times, Usain Bolt’s 9.58 seconds in Berlin 2009 is significantly faster than Jesse Owens 10.2 seconds in Chicago 1936. Surely that’s case closed, Bolt is comfortably the faster man and he would have won by a distance of 4.3m. However, when you consider the different equipment each uses, the picture becomes much less clear.

Jesse Owens set his time running on a track made of cinders (the ash of burnt wood) which would absorb his energy while running, wearing leather running shoes with nails used as spikes. He also dug holes into the track for traction at the start line. All of which would be seen as less than ideal today.

Usain Bolt meanwhile set his time on a polyurethane track, which would reflect his energy helping to propel him forwards, wearing lightweight running spikes, especially designed for the track he is running on and using starting blocks for traction at the start line. Using biomechanical analysis, it is estimated that Jesse Owens would be within one stride length of Usain Bolt if both run today and that is before considering the effects of the different quality of time keeping may have had on the results. When all that is taken into consideration, it becomes difficult to assess who actually was the fastest man in history.

The story is similar for cycling. We have previously covered how using carbon fibre bikes instead of the 1980s steel bikes has led to a 1 hour time difference in Tour De France completion times over the course of a modern race. But the difference is even more stark when looking at the world hour record, once considered the ultimate test of cycling endurance.

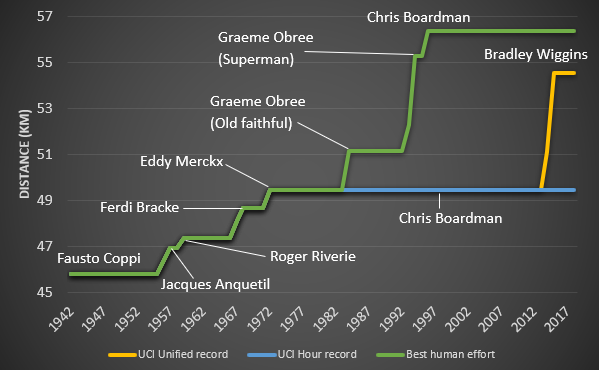

Advances in materials and design has effectively made a farce of the once prestigious hour record, to the point that the UCI has had to split it into three categories. The UCI hour record, set on a 1980s style steel framed bike, The UCI unified record, set on a modern individual pursuit bike and the best human effort, set on any bike.

Up until the early 1980s, the hour record was being set on fairly similar, steel frame bikes. Then throughout the 80s and 90s, Chris Boardman and the flying Scotsman, Graeme Obree, decided to reinvent the bicycle in the name of sporting excellence. That period coincided with the rise of carbon fibre, which allowed for new shapes to be achieved that were previously difficult to manufacture. Additionally, this period also the rise of aerodynamics creeping into sport.

Between the pair of them, they continually smashed the hour record, taking it up from the 49.437kM set by Eddie Merckx to 56.375kM. While this period did a lot to grip the public imagination for the world hour record and really added to the mystique, cycling purists were not happy with what the record was becoming.

Fearing that the hour record was now becoming a battle of technology, rather than of human endeavour, the UCI changed the rules to ensure that records must be set on a traditional steel frame bike. This decision effectively wiped out all records from 1972 onwards, Leaving Eddie Merckx again as the record holder of the hour record. Boardman again took on the challenge of beating Merckx record, but instead of beating him by almost 7km, with the old rules, the record increased by a mere 10m, showing once and for all the effect that developments in materials technology has had on sport.

Seeing how difficult it had become to brake the record and due to the fact that the record would now need to be carried out on outdated equipment that would seem alien to the modern cyclist, the UCI again changed the rules in 2014 to try and reintroduce the hour record into relevance. This time, using team pursuit bikes that are used at the Olympics. This has led to a new flurry of activity as rider after rider attempts to break the record, which as of April this year is held by Victor Campenaerts with 55.089kM. While extreme bike designs are stopped under the new rules, material and design can now have a large impact on results again. This is highlighted by the Australian team pursuit team gaining a 7% advantage in the Rio Olympics by changing the design of their chain rings.

While we continually state that we want to see a fair race showing off the ultimate of human performance, the question has to be asked, are we really seeing fair comparable races today? Drugs doping has rightly been outlawed and is frowned upon, but are we today seeing materials doping in sport? Is it unethical to allow athletes to compete on different equipment? i.e. are the athletes competing, or are the sports equipment manufacturers? And how far will it go? Will we potentially see a situation in the future, where humans physically alter their bodies in order to gain a competitive advantage over their rivals? Ultimately how much further can composites push human performance? I don’t pretend to know the answers to any of these questions, but it will be interesting to see how it all plays out in the coming years.

References

- Epstein, D. (2014). Are athletes really getting faster, better stronger?. [Youtube] TED Vancouver

- Froes, F. (1997). Is the use of advanced materials in sports equipment unethical?. JOM, [online] 49(2), pp.15-19. Available at: https://www.tms.org/pubs/journals/JOM/9702/Froes-9702.html [Accessed 21 Sep. 2018].

- R-TECH Materials article on how Composite Materials Revolutionised the Tour De France. 2017.